Hi, reader! We’re opening THE MAILBAG again for extra fun content related to my serialized novel DANCING AT THE ORANGE PEEL. The Mailbag holds my unexpected discoveries while writing, research and history bits, travel updates and photos, and much more.

I had fun with images for this one, so if you’re reading this in email, you’ll have to click “View entire message” at the bottom to keep reading.

Hang on for a deep dive into Americana inspired by Episode 7: The Promise. It isn’t necessary to read the episode first to enjoy this piece, but of course, I’d love it if you could.

Just getting started? Explore The Novel’s Episode Guide | THE Full MAILBAG

The Original 28

As Episode 7 of my serialized novel begins, nine-year-old Libby, her mother Gwen, and a family friend are just returning from an ice cream outing. Even though there’s an ice cream shop down the street, Libby has convinced the adults to drive out to their local HoJo’s on the main highway instead. It’s just that good!

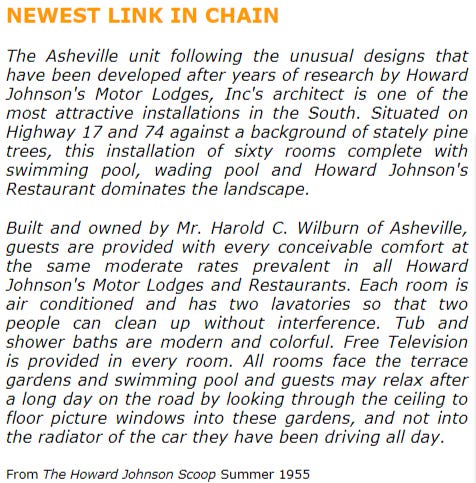

Howard Johnson’s restaurants and motor lodges began as an ice cream counter and newsstand inside a Massachusetts pharmacy in 1925. In my hometown of Asheville, NC, there were two Howard Johnson’s locations. The one shown below opened in 1955, as announced in the HoJo’s employee newsletter, The Scoop. Ooooo, free in-room TV!

The other HoJo’s I remember was on Hendersonville Road, not far from the entrance to the historic Biltmore House. That’s the one we went to when I was a kid and this location inspired the HoJo’s that Libby, Gwen, and Grant visit in my novel.

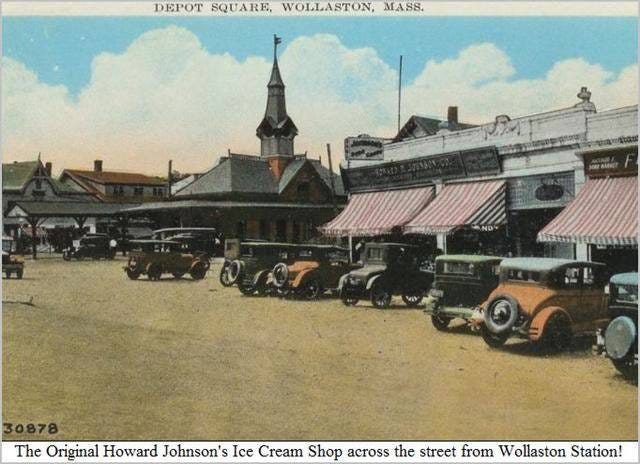

One version of the Howard Johnson’s origin story goes like this: Twenty-seven-year-old Howard Deering Johnson inherited a drugstore/soda fountain from his father, who had taken it deeply into debt. Another version has Johnson inheriting a cigar wholesale company, which he drove into debt himself and had to shut down. Then he took a job at a soda fountain to earn money to pay back the debt. Recognizing the soda fountain’s popularity, Johnson borrowed money to buy it when the owner died.

No matter how he originally acquired the business, he was certain he could grow it by selling the best ice cream. He experimented with taste and quality by hand-churning various recipes in the shop’s basement. He developed 28 superior ice cream flavors that soon had customers lined out his door.

During summers in the late 1920s, he sold his ice cream, along with hot dogs and soft drinks, from beachfront concession stands. Each year, his small business grew. Who wouldn’t want a cone from here on a hot summer day?

Eventually, Johnson convinced bankers he could successfully operate a family-style restaurant, and the first one opened in Quincy, Massachusetts. By happenstance, in 1929, the mayor of Boston banned a production of Eugene O’Neill’s “Strange Interlude,” a play including themes of mental illness, affairs, and abortion. Determined to stage the play, the Theatre Guild moved it to the Wollaston Theatre in Quincy, not far from HoJo’s.

Due to the play’s length of five hours, it was presented in two parts with a dinner break between, giving influential Bostonians time to experience their first taste of HoJo’s. They loved it and spread the word.

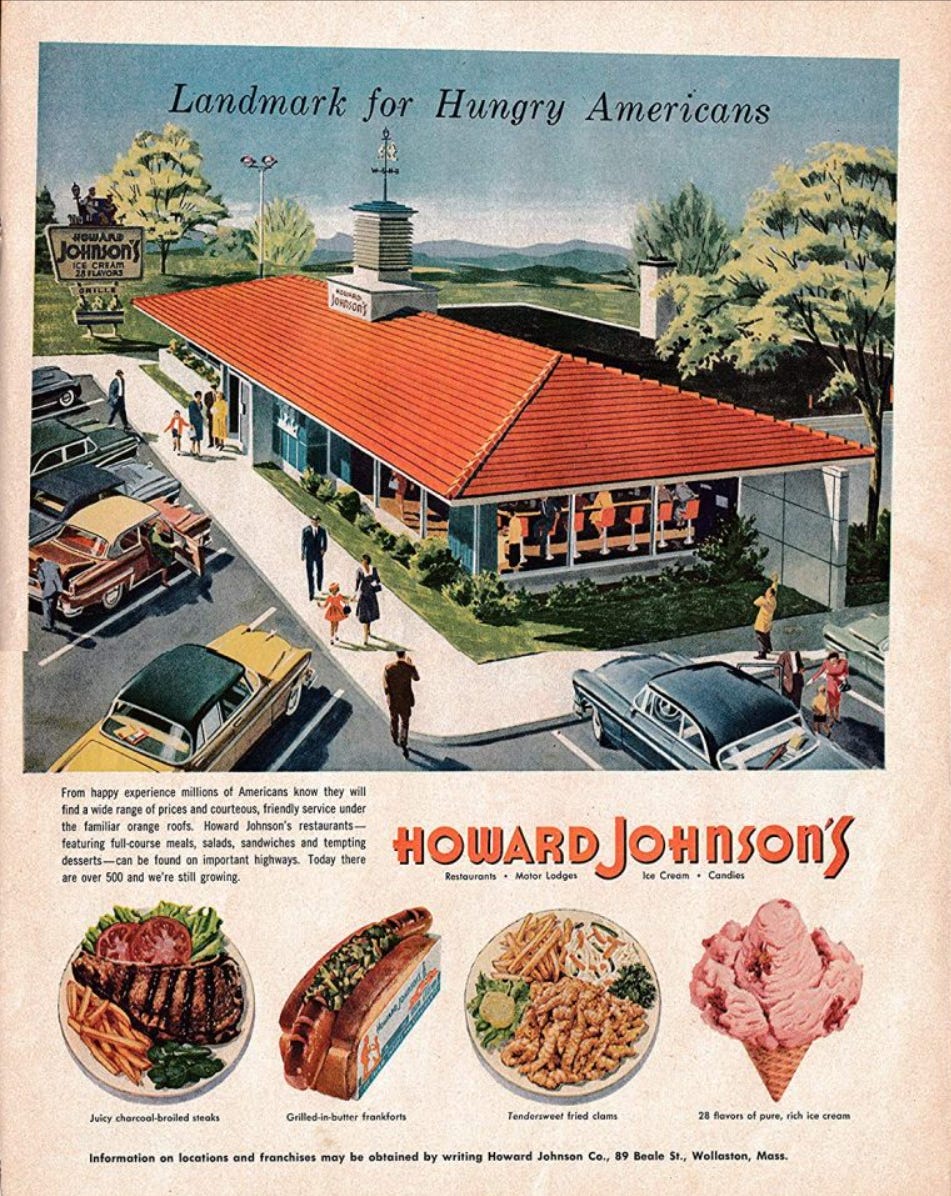

This success inspired Johnson’s vision to expand his food menu and open a second location, but the crash of 1929 kept that from happening. His plans were put on hold, but even during the Great Depression, he held firmly to his business ideas. He strongly believed the automobile would change the way people traveled, and they would need to eat along the way. So his dream altered slightly into one of creating a chain of reasonably priced restaurants along major highways.

There’s some dispute over whether Howard Johnson’s or A&W was the first restaurant franchise in the U.S. But by 1935, agreements between Johnson and a handful of restauranteurs led to 25 roadside ice cream and sandwich stands in Massachusetts under the name of Howard Johnson’s. By the late 1930s, more than 100 HoJo’s extended along the Atlantic seaboard from Massachusetts to Florida.

With rationing of gas, food, and supplies caused by World War II, and especially due to travel restrictions enforced during the war, many HoJo’s went out of business. Johnson was in a precarious financial situation once again, so to keep the company from bankruptcy, the restaurants began providing food for schools, military installations, and defense plants.

After the war, some restaurants reopened and new ones started. The iconic orange roof became a lodestar for travelers. To address a shortage of skilled chefs, as well as assure consistency and quality across all locations, Johnson instituted a system of processing and pre-portioning the food at a central plant and then shipping to restaurants for final preparation.

In 1953, advertising agency NW Ayer & Son, Inc. proposed the company’s first television ad campaign. The agency released a series of 15-minute films called “Howard Johnson’s Playtime Theater” with commercials featuring dancing ice cream cones and other animations, along with images of Howard Johnson’s restaurants. Also by 1954, Howard Johnson’s opened its first franchised motor lodge, located in Savannah, Georgia, and the restaurants had grown to 400 locations.

Johnson’s son, Howard B. Johnson took over the company in 1959 and, through the 1960s, HoJo’s was the leader of convenience-eating establishments along U.S. highways. Those original 28 flavors created by H.D. Johnson endured, and my character Libby wanted to try them all.

Through the 1970s, McDonald’s, Burger King, and other fast food restaurants carved into HoJo’s market share. Even though the company surpassed 1,000 restaurants and 500 motor lodges (including vending and turnpike operations and a robust manufacturing and distribution system), the competition proved too daunting.

H.D. Johnson’s son sold the business to a British company in 1980, and after that, the company went through a succession of corporate owners, including Marriott. In the 1990s, franchisees went to great efforts to maintain the viability of the original HoJo’s restaurant concept, to obtain the rights to the name, products, and recipes, and to continue doing business in their local markets, but gradually, HoJo’s restaurant locations up and down U.S. highways shuttered. The franchise group lost all rights in 2005, and the future of the remaining restaurants was dim.

Eventually, Wyndham Hotel Group acquired the rights to the Howard Johnson’s food business and hotel chains, and, in 2015, proposed a major facelift to bring back the brand. Few of those plans came to fruition.

Who knows who owns the original recipes for the ice cream now, but I’d sure be delighted to step back into 1968 and drive out to the main highway with Libby for a cone. We’d get to choose from HoJo’s original 28 flavors listed below. Wanna join us? Which flavor would you pick?

In “The Promise," Episode 7 of Dancing at The Orange Peel, Libby choses butterscotch. Maybe that’s her favorite flavor. Maybe not. If you’ve read along in the novel so far, what do you think she’d pick?

Thanks for going on this fun excursion with me. See how this article relates to my novel DANCING AT THE ORANGE PEEL by checking out Episode 7: The Promise.

More reading: The Novel’s Episode Guide | THE MAILBAG

Never miss an episode or the fun extras by subscribing…

I appreciate you!

Your grateful scribe,

This write-up on Howard Johnson's is nostalgic! Sadly, many of those cultural landmarks of my youth have passed from the scene.

Love this history! I grew up in Massachusetts and HoJo’s were everywhere. My high school,boyfriend and I used to skip Sunday mass to go get breakfast at HoJo’s. I was fond of the scrambled eggs with ham and a corn toastee. Thanks for bringing back some good memories of simpler times.